Reflections

Nacirema Lesson

For this lesson, I introduced students to Horace Miner’s text “Body Ritual Among the Nacirema,” which describes the bathing routines of a “North American group” using language that frames them as primitive, barbaric, and exotic. Toward the end of the lesson, students are shown that “Nacirema” is simply “American” spelled backward.

Planning this lesson helped me internalize that the measures I take to support students with learning differences are efforts that are universally beneficial to all students. For instance, when I first began modifying the text for my students, I created two unique reading packets. One version was more scaffolded, as it had comprehension questions interspersed throughout the reading and accentuated new vocabulary using a bold typeface. Later on, my supervisor pointed out that all students would likely benefit from the more scaffolded version of the text. This made me realize that I used to think that differentiating instruction for diverse learners was synonymous with creating distinct material for students who could benefit from additional support. What I now understand is that making these supports more widely accessible is often useful for many students.

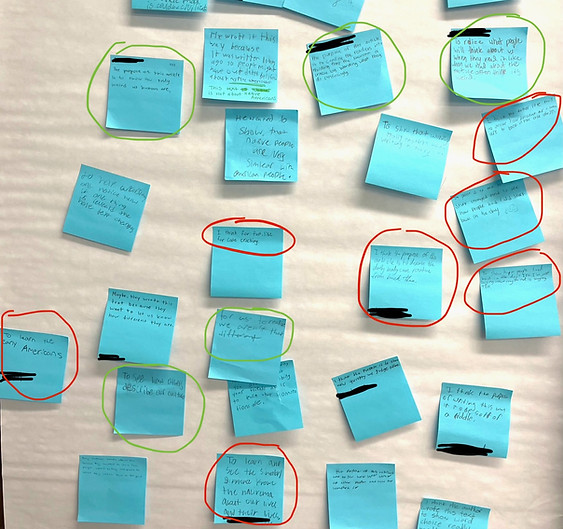

Another thing I learned from teaching this lesson is that the text has aged more than I realized. For one, it refers to egg-shaped hairdryers that were typical of salons in the 50s. Because I had explained that the text was written in the 1950s, some students mistakenly got the impression that the purpose of the text is to show the difference between Americans “back in the day” (as opposed to today). Other students believed that the text was describing Indigenous Americans (see images below for more). Instead, the purpose of this text is to show students how subtle differences in word choice can make a dramatic difference in the way people and cultures are portrayed. This text is useful for this goal because it describes cultural norms using words that make them unrecognizable to the very people who practice them. The fact that a few students misunderstood this key detail made me realize that they may not have seen themselves reflected in the text (beyond the purposefully deceptive language it uses).

Student "exit tickets" collected at the end of the lesson. Red circles indicate misunderstanding, green circles indicate excellent responses

For this reason, when I teach this lesson again in the future, I would like to incorporate examples of routines that are more tailored to my specific students. For example, our students are expected to write down their homework in their planners as soon as they enter the classroom. They are also only permitted to use the bathroom once they receive a specific, coiled bracelet from a teacher. Using elements of classroom procedure, I could write examples of statements that mirror Miner’s text, like this one:

“Every day, the young pupils carry larger loads [backpacks] to the special structure [school]. One by one, they walk under a blue arch [the doorway]. Next, they robotically navigate to a specific spot in a specific meeting room [classroom]. They drop their loads and remove a green scroll. Using ceremonial utensils [pencils], they copy the scripture [homework] written on the shiny surface [whiteboard].”

I believe that using examples that are more specific to students’ daily experiences could improve overall comprehension of the text. Another option is to have students complete the same exercise. Either way, I think that providing an example with a different context could help further cement how word choice can be manipulated to generate charged tones that impart specific opinions to readers.

An example of a superbly completed tone and framing worksheet

In the future, I would also like to incorporate more checks for student understanding throughout the lesson and introduce students to connotations, tone, and framing before reading the text. Though many students were able to grasp these concepts and find examples in the text, many had a hard time completing this worksheet.

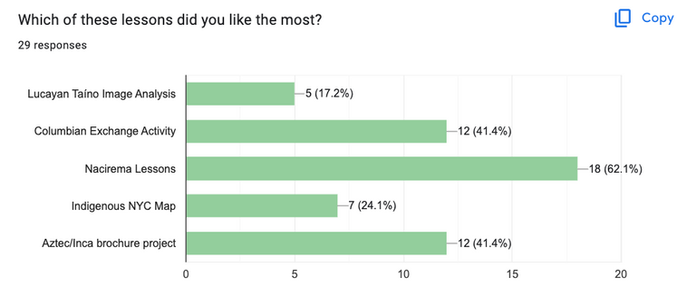

Overall, I think this lesson is one of the ones I’m most proud of during my time at LAB. Throughout all three lessons, both sections I taught were extremely engaged in the material and eager to discuss the text. Furthermore, I asked students to complete a feedback form about the projects and lessons I designed and a majority of students in both sections of the class ranked these lessons as their favorite. With the minor tweaks I have in mind, I think that this mini-unit could be something that I go on to teach for the majority of my career, as it reinforces critical thinking skills, shows students how academic texts can frame different cultures, and opens a dialogue amongst students regarding the cultural conventions that many of them grew up in.

Feedback form responses from one section of 7th graders

Mapping Indigenous NYC Project

Since students had spent the majority of their “Early Americas” unit learning about Indigenous peoples in other parts of the Americas (like the Aztec, Inca, Maya, Olmec, and Taíno,) I was eager to design a project which would require students to learn about the history of the Lenape in Manhattan and draw conclusions about how their presence here has impacted NYC today. For the second part of this project, students read about places in NYC that demonstrate the ongoing presence of Indigenous communities.

Gathering resources for this topic was extremely labor intensive, given that there was little information about many of the places I selected. As a result, it became very challenging to find resources that were similar in length and gave students enough information to write about. That said, these differences in length and complexity ultimately allowed me to naturally differentiate the lesson, by strategically creating pairs of students at similar skill levels and assigning each group a text based on my knowledge of their reading levels and interests.

At the beginning of the school year, each of our students wrote a letter to the teachers. In these letters, they wrote about their passions, favorite subjects, and any other personal information they’d like to share. As I’ve gotten to know students since then, I’ve learned bits and pieces about which neighborhoods they live in, where they spend their time over the weekend, and the kinds of information each student appears to be most fascinated by. It was extremely gratifying to hear students express excitement about the locations they were assigned and see them indicate their connections to these places throughout the reflections they completed after contributing to our class maps.

Another thing that allowed this project to be so successful is that I was able to collaborate with the Special Education teacher in my classroom to design a scaffolded worksheet guiding students through their analysis of their texts. This worksheet asked them to identify and define challenging words and find important quotes from the text. This exercise was quite useful in facilitating students’ close reading of their assigned texts and making the task of writing a paragraph feel less intimidating.

After reading through the students’ work, I found that many pairs did an outstanding job using their text to write detailed and significant paragraphs. At the same time, there were a significant amount of partnerships that had a very hard time crafting a clear topic sentence.

Thus, if I were to teach this project again, I would spend more time explicitly teaching paragraph writing skills. Though I expected the majority of our students to begin 7th grade with a foundational understanding of how to structure academic writing, it seems as though even my strongest students were unfamiliar with how to write a topic sentence. Since this assignment evaluated their ability to do this, I worry that I ended up assessing students for skills that were not explicitly taught beforehand-- leading some to meet the standard, but many to struggle more than they should’ve. Another way I could better facilitate the development of student writing skills is by allowing students to revise their writing or even peer edit.

Lastly, in the future, I will opt to have multiple pairs work on the same text/place so that all of the places on the map are similarly significant. This would also make it possible to have two pairs work to combine their paragraphs and/or revise their work together.

Examples of student reflections

Columbian Exchange Activity

For this lesson, I divided students into seven groups: North America, Central America, the Caribbean, South America, Europe, Asia, and Africa. Next, I rearranged the desks to mirror the geography of these regions. When students sat at their “region,” they found a variety of “resources” that were available in the area before the Columbian Exchange, as well as a recipe for a local, traditional dish. After reading about local “resources” (which included crops, animals, diseases, and technology,) the groups were instructed to physically get up and find resources from other regions, until they had acquired all the ingredients to create their dish. Each time they gathered a new resource, they took note of how this item actually got to their region and the impact it had on local populations and land. Some resources instructed students to bring home an additional item (such as Malaria from Africa, silver from South America, and Christianity from Europe).

All in all, many things worked in this lesson. For one, students were extremely engaged. To boot, their responses to reflection questions indicated that all students internalized a) the purpose of the Columbian Exchange, b) its positive and negative impacts on populations across the globe, and c) how the exchange of resources impacted the physical land. Another thing I appreciated about this lesson was that it allowed students to discuss their cultural backgrounds and relate their personal experiences to the content. In particular, I began the lesson by having students discuss their favorite dish/meal, what ingredients it requires, and where these ingredients are from (if they know). At the end of the activity, students were prompted to think back to these meals and determine whether it would have been possible to create this dish in North America prior to the Columbian Exchange.

I enjoyed reading their answers to this question, because nearly all of them mentioned specific resources mentioned during the activity, and saw the impact the Columbian Exchange had on their life! Centering the lesson around dishes from around the world also gave me the opportunity to affirm students’ cultural backgrounds. Though I did not divide students into regions based on where they are all from, I intentionally placed some students in certain regions because I knew they would be excited about the recipes they were assigned. It was really nice to hear their enthusiasm when they got their assigned dishes. I even overheard a few students say “I love mofongo/empanadas/gnocchi!” or “my mom makes this sometimes!” Though I am opposed to discussions about culture in school being limited to food and festivals, I do think that global cuisines can provide an excellent opportunity for students to bring their identities into their work and relate to academic material on a personal level.

Examples of "resources" at different regions. Text on the other side of each page describes how it traveled and how it impacted populations. (Blue resources came from the Old World, pink resources from the New World.)

Two examples of student reflections

Although this lesson did satisfy its learning goals, there were certain aspects of the structure of the lesson that I would like to alter if I were to do this again. First and foremost, though I tried to incorporate the exchange of diseases, ideas, and technology into this activity, the lesson’s primary task being centered around food made it difficult to emphasize the non-food related exchanges that were made at the time. Furthermore, dividing students into such specific regions made it so that some groups were able to read about more important resources than others (for instance, only two of seven regions learned about how the Columbian Exchange paved the way for the trading of enslaved peoples (since sugar and tobacco were the two resources which depended on the labor of enslaved people).

To ensure that all students receive this information, at the end of the activity each group shared about the most important resources that were brought to their region (and all other regions were instructed to take notes on what their classmates shared). Though I also took down notes on the board, many students either did not record this information at all or could’ve used significantly more detail when explaining the impact of these resources on various regions. For these reasons, I think it would be beneficial for all groups of students to read the same text about the most important resources (rather than conducting this like a jigsaw).

Most of all, I wish that the activity would have been accurate to the actual movement patterns of these resources. Instead, students in each group were instructed to move freely to get various ingredients. Unfortunately, this meant that students were physically retrieving resources from regions where people from their region did not travel to. Thus, if I were to do this activity again, I would select only the most important resources, diseases, and ideas that traveled across the Atlantic and have all students read about each of them. One way to accomplish this is by designing a board game where students draw cards that prompt them to move small resource cards across the board (which would be a map). It could also work to have the whole class reenact these exchanges together, having students move resources across a map on the board.

This lesson could also be strengthened by allowing students to make connections to previous units. A day before reading about the Columbian Exchange, students learned about the exchange of resources throughout Eurasia and Africa and the seafaring technologies used by voyagers in different areas. Earlier on in the semester, they learned about the agricultural practices of the Aztecs, Incas, and Lucayans in Central/South America and the Caribbean. Of course, all of the information they learned in these units can be applied to the Columbian Exchange. For instance, they know that the Aztecs made drinks with cocoa, so they must’ve had access to cocoa beans; Lucayans settled in the Caribbean but were originally from South America (so they brought food sources up North with them); Trade routes had been established between Europe, Asia, and Africa before Europeans traveled across the Atlantic (which explains why many resources native to Africa and Asia were brought to the Americas by Europeans). Since most of the content students have learned in the first few months of school could be reactivated in this lesson, I hope to be able to find a way to incorporate this information in the future.